| Home > China Feature |

Wang Hai

Wang Hai (王亥) was a charismatic businessman; in fact, he was the businessman who “invented” the concept of trade some 3,500 years ago in central China. As the chief of the Shang (商) tribe, he led his people to domesticate horses and oxen to transport goods. The trade made him the richest man of his time. Wang was also a smooth dancer who charmed the daughter (some say wife) of another tribal chief while he and his brother were invited for a stay. After the welcome feast, Wang was accompanied by the lady back to his room. But, his luck was about to run out. In the middle of the night, a guard snuck into his room, chopped off his head and dismembered his body into eight pieces. This no-so-delicate assassination was the first of such in recorded Chinese history.

So, why did he do it? The nameless assassin didn’t live to tell the tale, as he was soon captured and executed. Some believe he was just the jealous boyfriend of the girl Wang was bedding, but more plausible explanations claim the host or his greedy brother ordered the hit. In this case, the assassin played a minor role, but as long as there has been power and profit, there has been a need for an assassin’s skills.

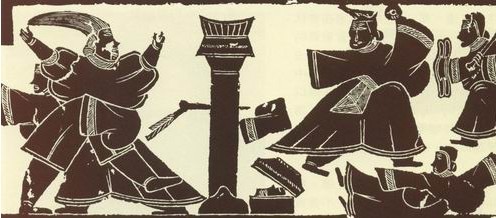

There have been a few occasions when the names of these cloaked and mysterious assassins have made history; some even demonstrated courage, chivalry, and heroism. Zhuan Zhu (专诸) was one such assassin in the late Spring and Autumn Period (770 B.C.-476 B.C.) who served the Prince Guang (公子光)of the State of Wu (吴国). The prince treated Zhuan and his mother with respect and kindness, so Zhuan decided to help his prince claim the throne by assassinating his cousin, the current king. This particular king was cautious of assassination, so Zhuan studied to be a royal chef, specializing in broiled fish, the king’s favorite. During a royal feast, Zhuan hid a thin, small sword inside the fish, and, when presenting his dish to the king, pulled out the blade and stabbed the king to death. Zhuan was killed on the spot by royal guards, but his wish did come true: the prince took the throne and became the famous King Helü (吴王阖闾), one of the five great rulers of the age. Zhuan’s loyalty to the prince revealed the Chinese assassin’s creed: 士为知己者死 (Shì wéi zhījǐ zhě sǐ, it is honorable to die for people who recognize and appreciate your worth).

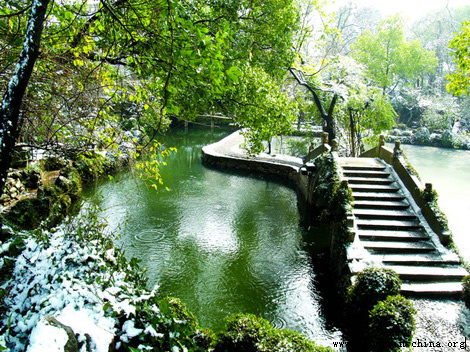

However, for Jing Ke (荆轲), who may be the most well-know (yet unsuccessful) assassin in Chinese history, loyalty and commitment required more than just appreciation. During the late Warring States Period (475 B.C.-221B.C.) when the State of Yan (燕国) was threatened by the powerful State of Qin (秦国), Jing, a skilled warrior, was recommended to the prince of Yan. The prince then shared his carriage, clothes and food with Jing to show his appreciation, in the hope that he would kill the king of Qin. For two years, Jing enjoyed all these luxuries without the slightest intention of repaying the debt. But, just when the State of Yan was on the verge of collapse, he offered a plan to assassinate the king of Qin. The prince and his friends all went to see Jing off by the side of Yishui River, where they bid farewell. He sang: 风萧萧兮易水寒,壮士一去兮不复还!(Fēng xiāoxiāo xī Yìshuǐ hán, zhuàngshì yī qù xī bù fù huán! The wind is soughing and the river water is cold, I will go on my journey with no return!)

With the head of a defected general from Qin and a map, Jing traveled to Qin’s court pretending to be a messenger offering surrender. Feigning surrender to get close to the king, Jing unrolled his map and pulled out a poisoned dagger. He attempted to grab the king’s sleeve and stab him in the chest. But, the sleeve tore. With the moment lost, chaos ensued and the king got the upper hand, stabbing Jing with his sword and ending his botched attempt. The surviving Qin king went on to not just conquer Yan but also all of the other five states, becoming the country’s major power. He was also the first man to call himself emperor, Emperor Qinshihuang (秦始皇). Though Jing failed to change history, he is admired for his courage and his solitary attempt to save his adopted state.

With tales of heroic feats, assassins were often romanticized. In fiction, there were even a few legendary female assassins such as Nie Yinniang (聂隐娘), the heroine in Pei Xing (裴铏)’s novel in the Tang Dynasty (618-907). The daughter of a general, she was kidnapped by a Buddhist nun at the age of 10 and trained to be an assassin.

Despite all the accounts of assassins in ancient China, most are obscure. Their motives, personal lives, and even the consequences of their actions were all kept out of sight, and it is, perhaps, this obscurity that intrigues us all. After all, the best assassins are the ones you never see.

Art

more

moreChina Beijing International Diet ...

Recently, The hit CCTV documentary, A Bite of China, shown at 10:40 ...

Exhibition of Ancient Chinese Jad...

At least 8,000 years ago, Chinese ancestors discovered a beautiful...

Longmen Grottoes

The Longmen Grottoes, located near Luoyang, Henan Province, are a tr...

Custom

more

more

print

print  email

email  Favorite

Favorite  Transtlate

Transtlate