more>>More News

- National Day

- ways to integrate into Chinese style life

- Should they be in the same university with me?!!

- Chinese Ping Pang Legend: the Sun Will Never Set

- A Glance of those Funny University Associations

- mahjong----The game of a brand new sexy

- Magpie Festival

- Park Shares Zongzi for Dragon Boat Festival

- Yue Fei —— Great Hero

- Mei Lanfang——Master of Peking Opera

Chna's Inner Mongolia

By admin on 2015-02-03

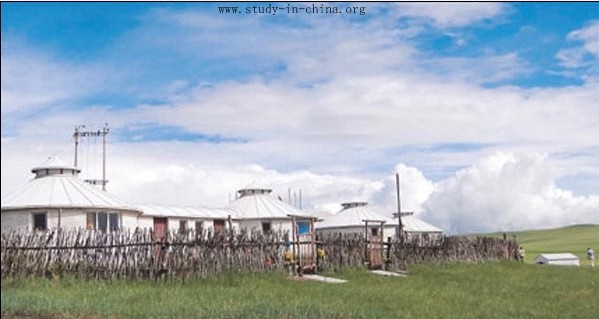

Chna's Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region beckons travelers with its fabled undulating fields of grass, fascinating Mongol customs and a scenic Russian border area that teems with trade. Yao Minji pays a visit.

We have a small forest, the Greater Hinggan Range, which extends 1,220 kilometers from north to south in Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region and Heilongjiang Province.

We have a small river, the Argun River, which extends 1,620 kilometers and divides China and Russia.

We have a small cadre, Genghis Khan, who established the Mongol Empire, the largest contiguous empire in history.

These sweeping understatements are used by locals of Hulunbuir City to introduce to us their hometown, humbly and proudly, when we arrived at Hailar District, the administrative center of the vast grassland.

The city, in northeastern Inner Mongolia, is larger than most Chinese provinces and is recognized as the largest city in the world in terms of area. Since it's so large, it often takes two or three hours to drive from one tourist destination to another.

The region is best known as the Hulunbuir Grassland, one of the most beautiful grasslands in the world where many nomadic groups, including China's Mongols, originated.

This is also where ancestors of Genghis Khan established their tribe and where the great emperor fought for many years and was said to be buried. Mysteries swirl around Genghis Khan, who conquered most of Eurasia in the 13th century. He is now considered a hero who united the ethnic tribes in the area; one of the biggest mysteries is the location of his burial site.

It's supposed to be somewhere in the grassland. Legend has it that after he was buried Mongols used dozens of horses to trample and flatten the ground, and it was guarded by hundreds of soldiers until the grasses at the site grew back and were identical to all the other grass. It became invisible.

But in order for people to worship there, herders killed lambs in front of their mothers so that the traumatized ewes would never forget the location. Whenever it was time for worship, people just followed the sheep to the slaughter site. After the sheep died, the location was hidden forever.

The grassland and the many towns and cities it encompasses have long been recognized as magnificent travel destinations but large-scale and planned tourism development in most parts only began in 2007.

That means there are limited tourism resources in terms of service, transport and accommodation. For those who don't like big development, commodification of Genghis Khan and Mongol culture, tacky souvenirs and shops, this is a good thing.

Even at the most popular destination, such as Hulun Lake, near the Shiwei Russian Ethnic Township, we didn't find street souvenir vendors that crop up everywhere else in China.

The majority of this place is very much how nature really is, without much human interference.

If you're looking for five-star hotels and luxury boutiques, this is not for you, though many hotels and restaurants have been built over the past five years. But be warned, five-star development is surely coming.

So see this wonderful place while it is unspoiled.

This is the place for those who are interested in nature and culture and have studied a bit of Mongol culture, its rules and taboos, beforehand. You can drive freely, stop whenever you like and wander around, eat whatever is available, stay wherever you can find lodging, even a yurt. It's a place for those who want to dump urban life for a couple of weeks and enjoy the beauty of the grasslands.

Before the trip, I had imagined a vast, intense green grassland with no borders, grass growing above knee-height and bending like ocean waves in the wind. I imagined intense green land and a dome of intense blue sky with white clouds. And, of course, herds of cattle, horses and sheep. A few simple Mongolian yurts.

During my six-day trip, I saw much of what I had imagined, but what was supposed to be beautiful, verdant prairie was rather disappointing. Nomads told us that July should be the best season when grasses grow high above the knee, but that hasn't happened in most parts of the great grassland in the past few years because of worsening drought, caused by industrial pollution from big coal mining (many surface mines also encroach on grasslands), over-grazing and increasingly dry weather.

When we arrived in early July, nomads had welcomed the first rain since spring and most of the grass was only ankle-high.

We also learned that Hulun Lake and Buir Lake, for which the grassland is named, have been shrinking for years. The storage level of Hulun Lake has dropped 4.6 meters since 2000, and the whole area of the lake decreased by 20 percent from its historic high; storage capacity is only half what it once was.

The shore of Hunlun Lake retreats around 100 meters every year, and is now more than 1,000 meters away from its original place. What was once a small cabin on stilts above the water now stands lonely at the shore, a few hundred meters away from the lake.

Over six days, we visited Hailar District, the administrative center; Ergun City, which contains a wetland park; Shiwei Russian Ethnic Township, and Manzhouli City, the busiest land port of entry in China (from Russia) and one of the most prosperous cities in northeastern Chin

Grassland pearl

Long known as the "Pearl of the Grasslands," Hailar District is one of the more populated areas in Hulunbuir Grassland and its administrative center.

More than 80 percent of the population is Han people, but respect for Mongols is evident in local policies and in daily life. All street signs are in both Mandarin and Mongolian. The largest newspaper publishes an edition in Mongolian.

Although Mongols in China have adopted some Han customs over hundreds of years, there are still cultural distinctions and taboos that strike visitors.

For example, dogs are loyal partners and friends for nomads, and one must never insult or beat a dog. Of course, dogs are not eaten, as in most parts of China.

Mongols have long believed in Tengriism, a Central Asian religion that combines shamanism, animism, totemism and ancestor worship. Ethnic Mongolians still pray to Munkh Khukh Tengri, the Eternal Blue Sky, and Mongolia (both the region and the country) is sometimes called the land of eternal blue sky. All things in the universe are revered and harmony between man and nature and among men is emphasized.

Visitors need to be sensitive and not show disrespect. For example, fire is especially revered, so it is forbidden to throw trash or cigarette butts into a fire. Do not step on exposed tree roots because that is considered an insult to tree spirits.

Arriving at a nomad's yurt, visitors are treated graciously, and guests are likely to be served noodles instead of meat, as a sign of respect. For people of the grasslands, grain is far more valuable than meat, which is common.

We drove for about 50 minutes from Hailar to a nearby grassland where Mongols reenact the scene of Genghis Khan and his tribe settling down. A dozen Mongolian yurts stand there.

We were welcomed with beautiful songs and three shots of strong rice wine. Before drinking, it is customary to pay respect to the "eternal blue sky" and the ground by first dipping a finger into the wine, rising the finger to the sky, and then point to the ground. The ritual is more elaborate for Mongolians.

The main activity at this destination is the worship of aobao or cairn (man-made piles of rock). Aobao means piles of stones in Mongolian. In the ancient times, when nomads crossed the grassland, they would leave rocks along the way as markers so they could find their way back. Over time more travelers added more rocks, which became tall piles of stones, or cairn, and they took on a religious significance.

Worshipping aobao is a major and serious activity. One picks up a rock from the ground and wraps it with a strip of cloth. One then makes a wish to the cairn and walks around it clockwise three times. The ceremony is finished when the stone is tossed on top of the cairn, adding to the pile of prayers.

At Hailar District, we also visited the World Anti-Fascist War Memorial, built at the site of a sprawling underground Japanese fortification. During 1930s, the area was occupied and fortified as part of Japan-controlled Manchukuo, a puppet state in northeastern China.

Japanese occupiers enslaved and then massacred more than 10,000 Chinese who built five huge underground bunkers in Hailar District. Since all the Chinese involved in the construction, including translators, were killed, it was not known until the 1970s, when the one and only survivor, who was left with one blind eye, told the story.

The highlight of the memorial is a 500-meter-long trip into the underground bunker, whose ceiling is 15 to 20 meters below the surface. The temperature inside is 20 degrees Celsius cooler than on the surface. The dark and eerie underground area includes bedrooms for generals, dormitories for soldiers, cipher rooms, kitchens and toilets, storage space for food and weapons and other spaces. Most of the huge and complex structure has not yet been developed by the district.

The memorial uses hundreds of pieces of sculpture to depict how the allied army of the Soviet Union, China and Mongolia fought the Japanese. The sculpture depicts soldiers, tanks and aircraft.

Manzhouli City

On the streets we saw more Russians than Chinese since Manzhouli City is China's biggest port of entry on land. There are frequently organized trips between the two countries.

The streets were filled with long-distance buses with Russian license plates, stores with Russian signs, and Russian tourists who were very familiar with the city.

Tourism is so lucrative that the city has attracted many souvenir-store owners from other parts of China, including the famous city of Yiwu, Zhejiang Province. Guides told us not to enter stores with signs only in Russian (Cyrillic ) since they are intended for foreigners only and the prices are more expensive. Some owners may refuse to sell to Chinese. Stores with signs in both languages are intended for visitors from all countries.

The guide told us that in 2006 and 2007, at the city's busiest, a train crossed the border every 10 minutes, mostly carrying wood and coal in bilateral trade (China selling wood from its Greater Hinggan Range).

The trade slowed in the global economic downturn in 2008. Today trains cross about every hour.

The downtown is so prosperous it can be called a metropolis, with striking night scenes of glittering lights. It's planned in an orderly street grid. Planners gave themes to each of a few major avenues and renovated buildings to match the names: Russia has an onion-dome, and other buildings are baroque, Italian and French.

Matryoshka (colorful nested dolls) Square is filled with matryoshka sculpture of all kinds and sizes. At night it's lighted up, creating a fairy-tale ambience.

Ergun City

Around three hours' drive from Hailar District is the Shiwei Russian Ethnic Township, selected as one of China's 10 Charming Towns by China Central Television in 2005.

The town of around 1,800 residents is separated from Russia by the Argun River. Around 63 percent of the population are of mixed Chinese and Russian heritage. The main attraction is a Russian-style dinner and performances by Russian dancers.

Visitors can take a cruise along the Argun River where a Russian town is visible in the distance. More tourists are arriving and many wooden inns were under construction to provide accommodation.

Ergun City also contains a wetland park, with an undisturbed national eco-system.

- Contact Us

-

Tel:

0086-571-88165708

0086-571-88165512E-mail:

admission@cuecc.com

- About Us

- Who We Are What we do Why CUECC How to Apply

- Address

- Study in China TESOL in China

Hangzhou Jiaoyu Science and Technology Co.LTD.

Copyright 2003-2024, All rights reserved

Chinese

Chinese

English

English

Korean

Korean

Japanese

Japanese

French

French

Russian

Russian

Vietnamese

Vietnamese