| Home > China Feature |

An Overview of Hong Kong Action Cinema

Hong Kong action cinema is the principal source of the Hong Kong film industry's global fame. It combines elements from the action film, as codified by Hollywood, with Chinese storytelling and aesthetic traditions, to create a culturally distinctive form that nevertheless has a wide transcultural appeal. In recent years, the flow has reversed somewhat, with American and European action films being heavily influenced by Hong Kong genre conventions.

The first Hong Kong action films favoured the wuxia style, emphasizing mysticism and swordplay, but this trend was politically suppressed in the 1930s and replaced by styles in which films depicted more down-to-earth unarmed kung fu, often featuring folk hero Wong Fei Hung. Post-war cultural upheavals led to a second wave of wuxia films with highly acrobatic violence, followed by the emergence of the grittier kung fu films for which the Shaw Brothers studio became best known. The 1970s saw the rise and sudden death of international superstar Bruce Lee. He was succeeded in the 1980s by Jackie Chan—who popularised the use of comedy, dangerous stunts, and modern urban settings in action films—and Jet Li, whose authentic wushu skills appealed to both eastern and western audiences. The innovative work of directors and producers like Tsui Hark and John Woo introduced further variety (for example, gunplay, triads and the supernatural). An exodus by many leading figures to Hollywood in the 1990s coincided with a downturn in the industry.

Early martial arts films

The Swordswoman of Huangjiang (1930) co-starring Chen Zhi-gong.

The signature contribution to action cinema from the Chinese-speaking world is the martial arts film, the most famous of which were developed in Hong Kong. The genre emerged first in Chinese popular literature. The early 20th century saw an explosion of what were called wuxia novels (often translated as "martial chivalry"), generally published in serialized form in newspapers. These were tales of heroic, sword-wielding warriors, often featuring mystical or fantasy elements. This genre was quickly seized on by early Chinese films, particularly in the movie capital of the time, Shanghai. Starting in the 1920s, wuxia titles, often adapted from novels (for example, 1928's The Burning of the Red Lotus Monastery and its eighteen sequels) were hugely popular and the genre dominated Chinese film for several years.

The boom came to an end in the 1930s, caused by official opposition from cultural and political elites, especially the Kuomintang government, who saw it as promoting superstition and violent anarchy.Wuxia filmmaking was picked up in Hong Kong, at the time a British colony with a highly liberal economy and culture and a developing film industry. The first martial arts film in Cantonese, the dominant Chinese spoken language of Hong Kong, was The Adorned Pavilion (1938).[citation needed]

Postwar martial arts cinema

Scene from the wuxia film Buddha's Palm (1964). The magic qi rays are created using crude hand-drawn animation.

By the late 1940s, upheavals in mainland China—the Second Sino-Japanese War, the Chinese Civil War, and the victory of the Communist Party of China—had shifted the centre of Chinese language filmmaking to Hong Kong. The industry continued the wuxia tradition in Cantonese B movies and serials, although the more prestigious Mandarin-language cinema generally ignored the genre. Animation and special effects drawn directly on the film by hand were used to simulate the flying abilities and other preternatural powers of characters; later titles in the cycle included The Six-Fingered Lord of the Lute (1965) and Sacred Fire, Heroic Wind (1966).

A countertradition to the wuxia films emerged in the kung fu movies that were also produced at this time. These movies emphasized more "authentic", down-to-earth and unarmed combat over the swordplay and mysticism of wuxia. The most famous exemplar was real-life martial artist Kwan Tak Hing; he became an avuncular hero figure to at least a couple of generations of Hong Kongers by playing historical folk hero Wong Fei Hung in a series of roughly one hundred movies, from The True Story of Wong Fei Hung (1949) through to Wong Fei Hung Bravely Crushing the Fire Formation (1970). A number of enduring elements were introduced or solidified by these films: the still-popular character of "Master Wong"; the influence of Chinese opera with its stylized martial arts and acrobatics; and the concept of martial arts heroes as exponents of Confucian ethics.

"New School" wuxia

In the second half of the 1960s, the era's biggest studio, Shaw Brothers, inaugurated a new generation of wuxia films, starting with Xu Zenghong's Temple of the Red Lotus (1965), a remake of the 1928 classic. These Mandarin productions were more lavish and in colour; their style was less fantastical and more intense, with stronger and more acrobatic violence. They were influenced by imported samurai movies from Japan and by the wave of "New School" wuxia novels by authors like Jin Yong and Liang Yusheng that started in the 1950s.

The New School wuxia wave marked the move of male-oriented action films to the centre of Hong Kong cinema, which had long been dominated by female stars and genres aimed at female audiences, such as romances and musicals. Even so, during the 1960s female action stars like Cheng Pei Pei and Connie Chan Po-chu were prominent alongside male stars, such as former swimming champion Jimmy Wang Yu, and they continued an old tradition of female warriors in wuxia storytelling.[citation needed] The signature directors of the period were Chang Cheh with One-Armed Swordsman (1967) and Golden Swallow (1968) and King Hu with Come Drink with Me (1966). Hu soon left Shaw Brothers to pursue his own vision of wuxia with independent productions in Taiwan, such as the enormously successful Dragon Inn (1967, aka Dragon Gate Inn). Chang stayed on and remained the Shaws' prolific star director into the early 1980s.

Art

more

moreChina Beijing International Diet ...

Recently, The hit CCTV documentary, A Bite of China, shown at 10:40 ...

Exhibition of Ancient Chinese Jad...

At least 8,000 years ago, Chinese ancestors discovered a beautiful...

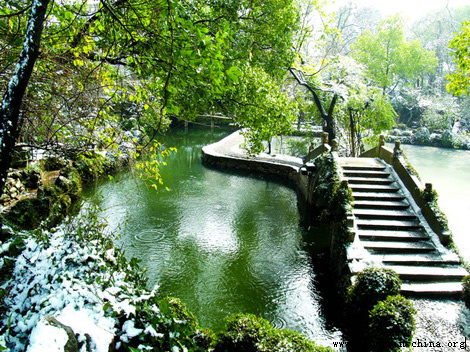

Longmen Grottoes

The Longmen Grottoes, located near Luoyang, Henan Province, are a tr...

Custom

more

moreWeb Dictionary

Martial Arts

Qigong getting popular as China goes global

"Going abroad" has become a popular phrase in China as its fast...

The Smiling, Proud Wanderer

The term "Xiao Ao Jiang Hu" (笑傲江湖), literally translated as Laughing...

Wuxia (Martial Arts) Novels

The wuxia novel is a Chinese novel genre, which features marti...

print

print  email

email  Favorite

Favorite  Transtlate

Transtlate