| Home > Living in China > Art |

2008 Beijing Olympic Games Opening Ceremony: Instrumental in Spreading the Word

August 8th, Beijing ?The 29th Olympic Opening Ceremony was a unique opportunity to introduce Chinese culture to the rest of the world. Furthermore, a vital element of the ceremony was its music, which featured many traditional Chinese instruments.

Chen Leiji, 41, was one of many musicians at the ceremony but he attracted greater attention because of the instrument he played immediately after the flag-raising ceremony. Guqin, a seven-stringed zither-like instrument, has been regarded as the epitome of Chinese music, philosophy and culture for 3,000 years.

Chen Leiji, 41, was one of many musicians at the ceremony but he attracted greater attention because of the instrument he played immediately after the flag-raising ceremony. Guqin, a seven-stringed zither-like instrument, has been regarded as the epitome of Chinese music, philosophy and culture for 3,000 years.

Born into a musician's family in Shanghai, Chen began learning guqin at age 9 and studied with master Gong Yi at the Shanghai Conservatory of Music before leaving for France in 1989 to study piano, composition and conducting.

His four-year trip to Europe not only provided him extensive experience with dozens of orchestras but also deepened his understanding of the Chinese music tradition.

"After learning Western music, which is very strict, I came to love the freedom of guqin," says Chen.

While the score in guqin music records the position and gesture of the hands, the rhythm is not dictated. As a result, says Chen, "each player can have his or her own understanding of the same piece".

Symbolism runs deep in guqin music reflecting its supreme ability to put man in touch with nature. Its strings, for instance, symbolize gold, wood, water, fire and earth - five basic elements of the universe. Emperors Wenwang and Wuwang, who founded the Zhou Dynasty in the 11th century BC, added two more strings to the instrument, which signifies the grave nature of this instrument.

Ancient Chinese scholars regarded playing guqin with a few friends in the pine forest or bamboo grove as one of life's greatest pursuits. It was also popular for the guqin player to chant or sing poems.

Ancient Chinese scholars regarded playing guqin with a few friends in the pine forest or bamboo grove as one of life's greatest pursuits. It was also popular for the guqin player to chant or sing poems.

At the Opening Ceremony, Chen played guqin with many other instruments for specially-written musical scores. These other instruments carry equally profound meanings in Chinese culture.

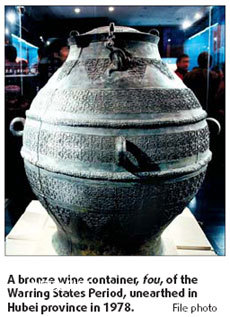

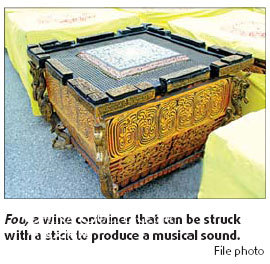

One of them was fou, a pottery wine container that can be struck with a stick to produce a musical sound. The Book of History written by Sima Qian (145-c.90 BC), said that when the Dukes of Qin and Zhao met in Mianchi (in today's Henan province) in 279 BC, the Duke of Qin pretended to be drunk and asked his counterpart to play se (a stringed instrument).

When the Duke of Zhao finished, a Qin historian on the site immediately noted that the Duke of Qin "ordered" the Duke of Zhao to play music, a gesture of one-upmanship.

Lin Xiangru, a wise prime minister serving the Duke of Zhao, asked the Duke of Qin to play fou, which was popular in Qin. When he was refused, Lin said: "If Your Highness doesn't play, in five steps, I am willing to spray the blood of my neck onto Your Highness."

Not far away, Lian Po, a great general of Zhao, had a big army massed on the border, ready to rescue his king if necessary. Finally, the Duke of Qin struck a fou with a stick. Lin noted this: On that day, the Duke of Qin played fou "for" the Duke of Zhao.

The interesting anecdote shows the importance of music in Chinese history. Ancient Chinese rulers had seen music as a way of enlightening people, and to use a modern expression, creating a harmonious society.

Back in the Zhou Dynasty that spanned eight centuries until 256 BC, music was part of a strict ritual system that upheld the social stratum. While the emperor enjoyed musical bells and chimed stones that lined on four sides, the dukes only had bells and stones on three sides.

Back in the Zhou Dynasty that spanned eight centuries until 256 BC, music was part of a strict ritual system that upheld the social stratum. While the emperor enjoyed musical bells and chimed stones that lined on four sides, the dukes only had bells and stones on three sides.

The requirements were not so strict by the time of the great philosopher and educator Confucius (551-479 BC), who saw this as a sign of a collapsing social order. Throughout his life, Confucius avidly learned about ancient rituals and music, which formed a main part of his teaching.

The oldest musical instruments found in China were the bone flutes unearthed in 1987 from Jiahu, Henan province. Dating back more than 8,000 years, the flutes were drilled with five to eight holes on bones of cranes and other animals.

It is fascinating that one of the flutes had been broken into three parts before being buried next to its owner. But the pieces were linked together with thin thread, showing the great love it once enjoyed.

As the animal bones vary in length and thickness, ancient musicians made marks on the bones to find out the best places to drill holes that would produce harmonious musical notes. Today, some of the bone flutes are on display at the Capital Museum in Beijing.

Many people mix the guqin with another stringed instrument called the guzheng, which was also featured at the Opening Ceremony with a dozen players. Producing a much louder sound with happier and faster tones, this instrument usually has 25 strings. While the guqin is an aloof solo instrument, only occasionally played with the se, ruan (stringed instrument) or xiao flute, guzheng has a taste of the grassroots, with folk tunes forming a big part of its repertoire.

Another instrument that generates rapid music is pipa. In the Dunhuang Mogao grottoes in Northwest China's Gansu province, one mural depicts a flying aspara, or Buddha's attendant, plucking the strings of a pipa behind her head while balancing herself on one foot.

Another instrument that generates rapid music is pipa. In the Dunhuang Mogao grottoes in Northwest China's Gansu province, one mural depicts a flying aspara, or Buddha's attendant, plucking the strings of a pipa behind her head while balancing herself on one foot.

This mural was probably inspired by the performances in the imperial court of the Tang Dynasty, which has inspired a lot of the costumes and scenes in the Opening Ceremony. While imperial music in the Zhou Dynasty had been solemn and ritualistic, Tang rulers were more down to earth and pursued extravagant recreations.

Also in the ensemble was the sheng, a reed pipe wind instrument whose history also goes back for thousands of years. In the Tang Dynasty, the sheng had 17 pipes, although another two could be added when necessary.

The Olympic Opening Ceremony again displayed the efforts of modern Chinese musicians to create new music with ancient instruments.

"Music is a genuine universal language that knows no boundaries," says Chen, who also teaches students the instrument from his guqin studio in Beijing.

Art

more

moreClassic Chinese Handicraft:

Porcelain pillows, as classic Chinese handicraft,

Chinese Treasures Returned from

As witness of Chinese culture and custom, countless treasures

The lost legacy: classical music

Accompany by the long history of China, Chinese classical music

Customs

more

moreChinese Kungfu

Kungfu Taste: Learn Martial Art in Shaolin Temple

The mention of Shaolin Temple conjures up images of a quiet and

Keet Kune Do will reappears on screen: BRUCE Lee and

The Legend of Bruce Lee is shot by China Central Television

The Road to the Olympic Games for Wushu

Wushu, also called kungfu, martial arts, is attracting more and more

print

print  email

email  Favorite

Favorite  Transtlate

Transtlate